What is Kabuse (Tea Shading)?

What is Tea Shading?

Tea shading is the process of covering the growing tea plants a number of days before harvesting.

It is a traditional Japanese way of cultivation.

Depriving the young tea buds of the sun changes their appearance and taste.

Resulting in a mellow green tea with little to no bitterness compared to sun-grown tea.

The Origin of Tea Shading

Local tea farmers in Uji (one of the best cities for authentic matcha) say people of the region were already used to covering tea leaves in the 15th century.

The tea plants' buds are very sensitive to the cold.

So when winters were particularly long, farmers of the time would cover the new shoots with straw and reed.

It was a way of protecting them from frost.

The exact period when the Japanese started shading tea bushes for the purpose of changing the leaves’ taste is unknown.

According to Mrs. Hasimoto Motoko in her book The History of Japanese Tea (日本茶の歴史), it might have been during the Tenshô Era (1573-1592).

So somewhere along the end of the 16th century –

the Japanese started to notice the difference in taste and linked it to the covering of tea leaves.

Extra Info: Up until the regular use of shading, matcha was made with regular sun-grown tea leaves and must have tasted quite bitter compared to the mellow matcha we know today.

3 Tea Shading Methods

When spring comes and the young tea buds are visible, farmers can start the covering process. There are 3 main types of shading that are used. Listed below are the methods in order from least to most preferred.

Jikagise, the direct covering method.

Kanreisha Tana, canopy shading using a black tarp.

Honzu Tana, the traditional bamboo and reed canopy shading.

1 - Jikagise (Direct Covering)

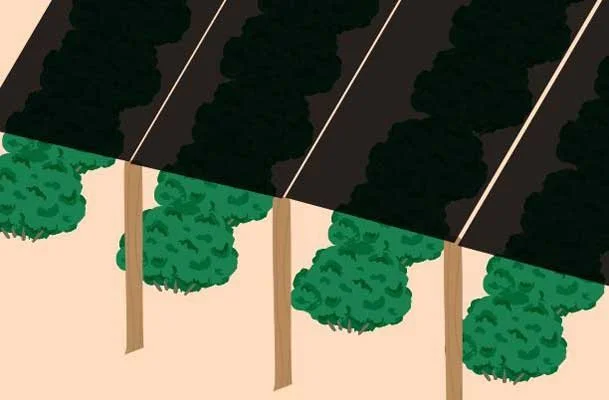

This is the most common covering process used today is Jikagise, likely because this style of shading is easy and inexpensive. The rows of tea plants are draped with a large black plastic covering with small holes.

To make Matcha and Gyokuro green teas, farmers usually use a covering blocking 70 to 80% of the light. After one week, they add a new layer that can take this number up to 98%. Of course, these percentages and timelines can vary from farm to farm.

Here is what directly shaded tea plants look like:

Smothering the tea bushes like this means air and moisture can hardly circulate inside. Plus, direct contact with the plastic cloth can make it difficult for new shoots to grow freely.

So farmers have to be careful not to tighten the covering too much… though overall this method usually produces lower-grade shaded green teas.

2 - Kanreisha Tana, (Canopy Covering)

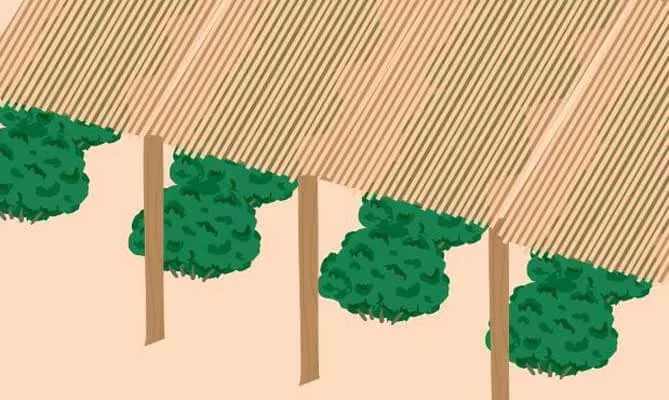

Canopy shading is the Japanese traditional method and gives the best results in terms of quality because it allows the tea bushes to grow without restraint, and provides more airflow. This shelf-like structure erected above the top of the tea plants is known as Tana.

There are 2 styles of canopy shading:

Kanreisha uses one, then two layers of the same black cloth as the direct shading method, supported by wooden or metal poles.

Honzu or “straw mats method” uses reed mats supported by wooden poles, and covered with straw.

For this point, we’ll focus on Kanreisha-style shading.

There are a number of reasons that canopy shading (Kanreisha) is superior to direct shading (Jikagise.) The shelf allows for more airflow, less heat, and less physical striction on the plants. The shoots point upwards, reaching to the little light filtering through the black tarps - and the physical upwards shape of the shoots makes hand-harvesting easier.

Kanreisha, like Jikagise, utilizes a black plastic tarp that is reusable from season to season, unlike Honzu-style shading. This greatly affects the final cost of the Matcha.

2 - Honzu Tana, (Canopy Covering)

The Honzu canopy style is the most ancient but is tremendously difficult to implement. Rather than using plastic tarps, Honzu utilizes traditional materials such as bamboo and reeds. It is also the most valued of the three shading methods:

Honzu shading uses only natural materials and filters light in an unpredictable way, similar to natural light filtering through the leaves of trees.

The reed mats allow for a fine adjustment of how much light goes through (reducing it after one week, then two weeks of shading.)

While this method is the most revered and produces the highest caliber of tea (usually reserved for Gyokuro or Matcha) there are a number of downsides.

Building up the Honzu structure and covering hundreds of rows of tea bushes takes tremendous manpower, skill, time, and effort.

The materials can not be reused from one harvest to the next.

The structure can be disturbed, especially when the reed is first placed on top of the canopy and before it rains (thus fixing the reeds to the structure.) Strong winds or storms can ruin hundreds of hours of work.

The Honzu style of covering is pretty rare, especially when looking for commercially available Matcha outside, or even inside, Japan. Teas produced with Tana-style shading are more expensive than direct shading, but Honzu enters another league of costs, due to the above factors.

Natural Tailoring

When you see tea fields in Japan, they are mostly made of small round bushes which are very uniform and visually striking. This is due to regular trimming, and specifically, the machines that are used to trim.

One of the more common machines is known as the Sentei ki, which looks like a curved lawn mower that’s held above the tea bushes on both sides by the producers. That curved shape of the machine is what gives the bushes their uniform, curved shape during their regular trimmings (and harvesting, too.)

Almost all tea farmers use machines to harvest their tea leaves. Handpicking (known as Tezumi 手摘み) is done on less than 5% of tea in Japan. Producers need the branches to be all the same size in order to cut only the top leaves.

Handpicking is of course preferred as it makes sure:

Only the youngest leaves (2 to 3 per stem) are picked

The leaves aren’t damaged during harvesting

So handpicking means no need for trimming, and that is why you can also see tea bushes growing kind of ¨wild.” Some even become almost as tall as humans! In this case, the only way to cover the tea plants is by canopy shading. Shaded teas produced with the honzu method and picked by hand are thus the rarest, but also the best you can find.

4 Types of Japanese Shaded Teas

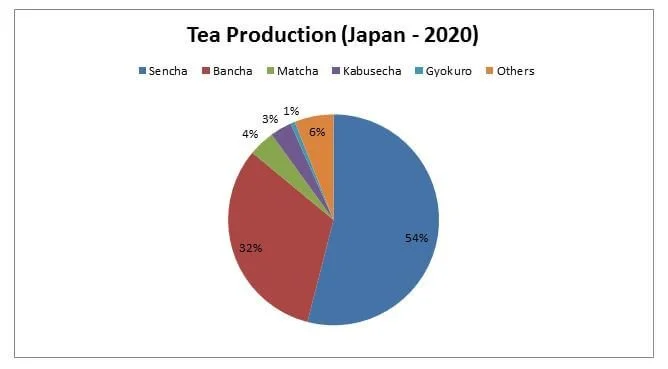

Shaded green teas are much rarer than sun-grown tea in Japan. According to the Japanese Association of Tea Production, only about 8% of the country’s tea in 2020 was shaded tea.

There are 3 well-known traditional Japanese shaded teas, plus one new member that recently made its appearance on the market.

1 - Matcha

Most people recognize what makes Matcha unique is the fact that it’s ground into a powder. This is true, but there are also powdered green tea that is not Matcha.

In addition to being ground, Matcha is also shaded. After being shaded, harvested, and ground into powder, Matcha is prepared by whisking the tea powder in warm water.

The tea particles will not dissolve but will keep floating inside the water, so it is the only tea that you actually ¨eat¨ as opposed to just brewing it.

To make matcha, farmers can shade the tea plants anywhere from 20 to 60 days before picking. The unground leaves that are eventually stone-ground into Match are known as Tencha. To find out more about matcha and how it is grown, you can take a look at our dedicated article The Matcha Plant.

2 - Gyokuro

Gyokuro is often considered the highest quality loose-leaf green tea in Japan. To put it simply, it is a high-grade shaded sencha.

Sencha as a refresher is a Japanese sun-grown green tea, the most consumed in Japan that is generally not shaded. Gyokuro on the other hand is shaded for at least 20-30 days before harvest. It has a deep green color and a very smooth taste with savory notes (Umami.) The taste profile of Gyokuro is a bit similar to matcha.

3 - Kabuse Sencha

Kabuse sencha literally means ¨covered sencha tea.” If Gyokuro and Tencha (Matcha) have a long shading time, Kabuse Sencha’s is shorter with a shading duration of 7 to 10 days prior to harvesting.

When you think of it, it’s a bit like a mix between Gyokuro and regular sun-grown Sencha. Kabuse sencha has a light umami flavor thanks to the short shading but it still retains some bitterness too.

4 - Hakuyoucha

Hakuyoucha is a relatively new kind of shaded tea that appeared during the 2010s. It is also called white-leaf tea (but it’s green tea, not white tea!)

To make Hakuyoucha, farmers need to cut almost 100% of the light while covering the tea leaves. This means using 3 layers of covering (each one 98% light-shielding) in total.

The tea plants must be shaded at least 2 weeks prior to harvesting and this intense covering process gives a tea with:

A very pale color (almost white)

An intense umami flavor and no bitterness

Tea Plants in the Sun

To understand how shade affects green tea – it's important to first understand the relationship between the sun and the tea plants.

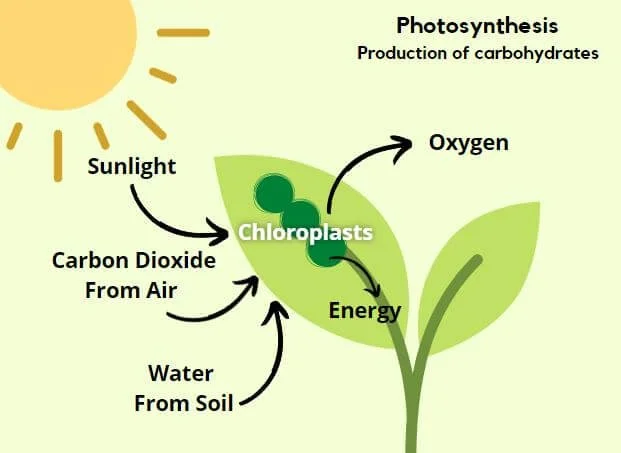

Photosynthesis

Plants are truly amazing, they are capable of producing their own ¨food¨, meaning carbohydrates. Carbohydrates are the starches, sugars, and fibers that give plants energy. To produce carbohydrates, most plants use photosynthesis. This process allows them to convert light energy into chemical energy and produces oxygen as a byproduct, which is rejected outside and enables us to breathe.

The Camellia Sinensis plant (tea plant) is no different. Tea leaves contain components named chloroplasts. Inside those chloroplasts, you find 2 types of molecules in charge of capturing light:

Chlorophylls are responsible for the green color of the leaves

Carotenes/carotenoids, which collect light energy and transfer it to chlorophylls

Basically, this is how it goes:

The plants can use or stock the energy produced. So in order to grow, the tea plants mainly need 3 things:

Water

Light

Carbon dioxide

How Tea Plants Regulate their Intake of Light

Tea plants can collect light energy via chlorophylls and carotenoids, but there is another compound present in tea that has an impact on UV sunlight: catechins. Catechin is a type of polyphenol found in green tea, which has been linked with various health benefits and antioxidant properties.

Catechins have a photoprotective function, meaning they can protect tea plants from harsh UV light. While tea plants need light for photosynthesis… Too much light can be detrimental and cause:

Dehydration

Leaves damage

To avoid this, tea plants use several protection mechanisms:

Moving the chloroplasts inside of the upper leaves so they don’t face the sun directly.

Using catechins as sunscreen to protect the tea leaves.

Carotenoids can release the excess energy they absorb as heat.

Chlorophylls also transfer their extra energy to carotenoids to be dissipated as heat.

Notes: Scientific research suggests this impressive sunscreen effect of catechins in tea could help prevent skin diseases related to UV radiation in sunlight when taken orally.

3 Ways Tea Shading Affects Your Tea

Light is crucial to the development of the Camelia Sinensis plant, but what is the effect on the plant when you almost completely deprive it of the sun? We covered in this article that some shading methods block up to 98% of its light!) Beyond the plant, what impact does shading have on your cup of green tea?

Here are 3 notable effects:

1 - It Changes Tea’s Chemical Composition

It all comes down to the natural stress response inside the tea plant. Low photosynthesis means tea plants can’t produce the energy (carbohydrates) they need to survive anymore. To cope with the situation, tea plants will:

Increase their production of chlorophylls and carotenes/carotenoids to boost photosynthesis with the little amount of light they receive.

Go through proteolysis, meaning they break down unneeded cell proteins into amino acids such as L-theanine and methionine to produce more energy.

Since catechins are a kind of protection from the sun, it doesn’t serve any purpose here. So the plants will both transform them into amino acids, and reduce the production of additional Catechins from amino acids, such as l-Theanine (more on this soon.)

Notes: Amino acids are the building blocks of protein. Protein is essential for life, and amino acids are necessary for protein synthesis. They also help to regulate many important cellular processes, including growth and metabolism in both animals and plants.

Here is a comparison between the compounds of 2 famous Japanese teas:

Matcha (shaded)

regular sencha’s (sun-grown):

To sum up, the covering process increases the concentration of:

Chlorophylls and carotenoids

Various amino-acids

And it decreases catechins inside the tea leaves.

2 - It Changes Tea’s Taste and Aroma

Shade has a direct impact on the flavor profile of green tea. In fact, natural shading (trees, fog) has already been altering tea’s taste even before the Japanese noticed there was a categorical difference before intentionally shading with coverings.

Artificial shading methods are more intense than natural shading… tea shading influences compounds that directly contribute to the taste, aroma, and overall mouth-feel of your tea:

So the distinctive mellow and umami flavor of shaded teas like matcha and gyokuro comes mainly from the amino acid known as L-theanine. The nori seaweed-like aroma (Ooika, 覆いか) Japanese associate with shaded green teas comes from methionine.

Overall, shaded plants have fewer catechins which result in tea with little bitterness. Other compounds (caffeine, carotenoids) can also subtlety influence the final taste of tea.

In Japan, green teas with the most umami tend to be considered of a higher standard. The quality and taste of a shaded tea will also depend on:

How long it was shaded (the longer, the more flavorful the tea will be.)

How it was shaded (canopy covering is more desirable than direct covering.)

When it was shaded (early spring is considered the best time.)

Where it was grown (micro-climate known as terroir.)

3 - It Changes the Tea’s Appearance

The covering process stimulates the production of chlorophylls within the tea leaves. It’s a way of boosting photosynthesis. And chlorophyll is the main pigment responsible for most plants’ green color.

Geeky info: Chlorophylls present in plants and leaves absorb light in the blue and red spectrum, but they reflect green light. That’s why tea leaves appear green to our eyes.

So shaded teas have a more pronounced green color than sun-grown teas. This is why high-quality Matcha tends to have a vibrant neon-green-like color. The only exception is Hakuyoucha, which turns a very pale color.

But there is more, the covering process slightly changes the physical form of the leaves. In order to maximize exposure to sunlight, the young leaves expand their surface. It results in wider, rounder, and thinner leaves.

However, the overall leaf density of the tea bushes tends to decrease.

Notes: Gyokuro leaves are so thin and tender that the Japanese sometimes eat them after brewing with a dash of soy sauce, just like you would eat spinach. (I tried it, and it’s actually very tasty)

FAQ

Can Tea Plants Grow In Shade?

Yes, tea plants can grow in shade. Farmers purposely cover their tea fields anywhere from 1 week to almost two months before harvesting. Usually, 70 to 95% of light is efficiently blocked. This process is used to make matcha for example. However, tea plants need a minimum of light to grow or they will eventually die.

What Does Shading Do to a Tea Plant?

The tea leaves can use chlorophylls to convert sunlight into energy, which they use to develop. This is photosynthesis. When faced with a light deficiency, the leaves will:

Produce more chlorophylls to boost photosynthesis

Transforms its useless compounds into energy

Those changes impact the final taste and appearance of shaded teas. Making them mellower and greener in color.

Why Only Green Teas are Shaded?

Tea shading increases the production of L-theanine and decreases catechins inside the tea leaves. This gives an umami-rich tea with low bitterness. There is no tradition in shading leaves to make teas like Wu Long (Oolong) tea or Red tea (known as black tea in the west.) Those teas need oxidation (using catechins) to get their typical sweet, malty flavor.

Drinking Good Tea Together

Nope, matcha’s flavor profile doesn’t come from magic. It’s all science and a long legacy of trial & error, and masterful craftsmanship. Shading is the key to making the tea plant produce its unique taste and aroma. But tea shading alone will not be enough to guarantee the quality of matcha.

There are so many other factors to consider such as:

The terroir (growing location) of the tea.

How it was harvested, processed, and stored.

And even how the Matcha is ground into powder - be it traditionally stone-ground or economically commercially milled.

If you want to know how to differentiate good from bad matcha – I encourage you to take a look at our article Ceremonial vs Culinary Matcha.